Among the pioneers of Polk County were several named Cory. I use the term pioneer in its strictest sense, for the old Pioneers’ Association will not admit any to the distinction who came to the county after 1848-49.

The Corys came early in 1846, before the state was admitted to the Union, from Elkhart County, Indiana. From them, the well-known Cory’s Grove, a beautiful belt of timber which extended out from Four Mile Creek, was named. They made their claims in what was then Skunk Township, put up log cabins, and at once began to develop the barren prairie. At that time, Polk County was not laid out in civil townships, the first Board of County Commissioners having simply divided the county into six townships for election purposes. Skunk Township embraced what now comprises Douglas, Elkhart, Franklin, and Washington townships.

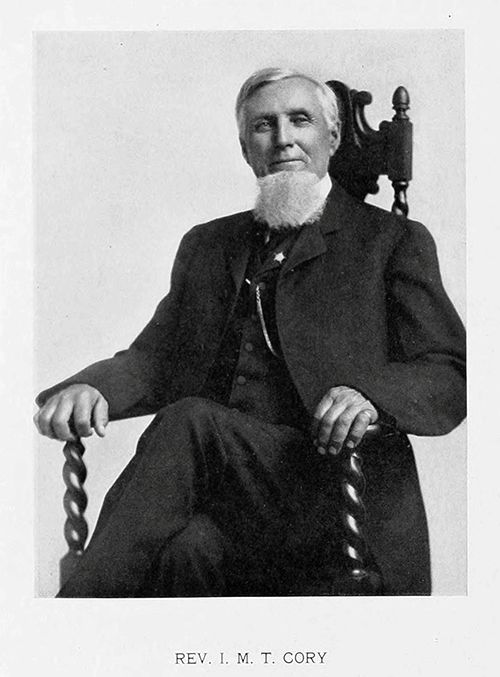

The new-comers wrote to home friends most glowing accounts of the new country, and the place of their adoption; that sometime the Capital of the state would be removed westward to a more central point, and that Cory’s Grove was just that point. Accordingly, early in October, 1846, more of the family started for the Promised Land, and among them was Isaiah Martin Thorp Cory—I think that is all the name he brought with him—a lad of nine years. They came, with horses and oxen, through Vermillion County, Illinois, crossed the Mississippi at Burlington, camping wherever night overtook them, with only one mishap, the drowning of an ox while fording a stream in Illinois. From Burlington, they followed the route used by freight haulers to “Uncle Tommy” Mitchell’s tavern, the resting-place of pioneers on entering Polk County. Skunk River Bottoms was crossed by good management and a severe struggle in its cavernous mud, and on the second day out from “Uncle Tommy’s” they reached their destination. The outlook was not very attractive, for, said Isaiah one day: “There was nothing there but Indians, deer, elk, turkeys, otter, beaver, and ’coons, but there was not a rabbit or rat in the whole county.”

The first demand was for shelter. A small log cabin was put up, the walls chinked with mud, and a chimney built of sticks and clay. Isaiah passed his boyhood days going to school and to mill with a sack full of grain before him on a horse. His leisure hours were devoted to fitting himself for active business and preaching.

In 1848, the Corys, with their accustomed energy and enterprise, decided to have a township more circumscribed, with some form of local civil government. They accordingly held a meeting organized a township, named it Elkhart, in honor of their Indiana home, and elected officers. The meeting was held at the base of a large boulder brought down from the far North by glacial ice, and which, by the subsequent cutting and carving of territory, is now the northeast corner stone of Douglas Township. That was the first civil township organized in that part of the county.

Skunk River runs through that section, and there are also several small streams. It was, in the early days, a favorite resort for hunters and trappers, as fur-bearing animals abounded.

Bands of Pottawattamie and Musquakie Indians, the latter remnants of the Sauk and Foxes, who refused to go to Kansas when the tribes were removed from the reservation around Fort Des Moines, frequently visited it, and, though considered peaceable, they caused considerable uneasiness in the Settlement, which was isolated, being the farthest north in Skunk Valley, for they were sometimes impudent and threatening, especially if none of the male members of a settler’s family were present. There was constant alarm among the women and children, who had little knowledge of Indians except as savages, for, however peaceable an Indian may be, when soaked with '‘fire water,” he is mighty uncertain. With few exceptions, bucks, as well as squaws, would drink it if they could get it. “Whiskey” was usually the first word they learned to speak in English. The women and children could not be divested of their fears.

Isaiah probably has not forgotten the Winter of 1848, that of the deep snow and severe storms, in which occurred the only real Indian scare in Polk County, of which I have any knowledge, and it occurred in his Settlement. The snow was so deep, and the blizzards so frequent, it was nearly impossible for settlers to communicate with one another, or get anywhere for several weeks. A band of Musquakies had camped near Cory’s Grove; the snow and storms had prevented them getting game for food, and they only escaped starvation by begging from the settlers corn, potatoes, and the carcasses of farm animals that had died from exposure to the elements.

One day, they came to the Settlement greatly agitated and excited, declaring a large party of Sioux was coming to take them, and massacre the whole Settlement. They urged the settlers to flee and save their lives. So intensely vehement and excited were they, the settlers were of course greatly disturbed, though doubtful of immediate danger. But, soon after, they were shown a campfire some distance away, in the northwest, which was certain evidence of the approaching Sioux. Instantly, the Settlement was aroused, and hurried preparations were made for protection and safety. The women and children, with everything that could be used for defense, were gathered at the cabin of J. W. Cory, where they were soon joined by the Musquakies, who volunteered to help defend the garrison. Not long after, Sioux scouts were seen in the grove not far away, and the shrill war whoop was heard. The women and children, paralyzed with terror, huddled close to the floor in a corner of the cabin, expecting every moment to hear the crash and cry of onslaught, not daring to make a sound for fear of adding to the terror of the situation. Every few moments, something occurred to intensify the horror. The men had equipped themselves as best they could for defense, and were stationed at the most vulnerable points, prepared for the worst.

Early in the evening, the Musquakie begged that their squaws and papooses, left in the tepees some distance away, be taken into the house with the white women and children, but it was refused. They were finally permitted to go into a rail pen near the cabin, where they were covered with straw. The squaw movement was also another cause of alarm and suspense, fearing there was treachery in it.

The night wore on—a night of absolute horror and suspense no pen can describe, the memory of which time will not obliterate from the minds of that little group. It was the longest night they ever passed.

Finally, when daylight began to dawn, and all was quiet, the Indians were charged with trickery, but they firmly denied it, declaring they had seen Sioux in the timber. Soon after, the squaws began to crawl out of the straw pile, and the chief’s wife declared she had seen and heard the Sioux, whereupon one of the bucks, known as Mike, told her she lied, that she had not seen a Sioux. He turned to go away, when she quickly drew a knife and made a savage thrust at him, which he parried with his arm, and then struck her across the chest. She started to run away, when he siezed (sic) her, took her knife from her, and plunged it and his own knife into her back, and she fell to the ground. Mike then fled, but was pursued by the chief and his son, amid great excitement of the settlers and Indians. The trio had not gone far when the sharp crack of two rifles was heard. But Mike outwitted his pursuers by spreading out his blanket at one side, and the bullets went through the center of it, missing him. He surrendered, a pow wow was held, and, after a long talk, it was agreed that he give twelve ponies to the chief for the injuries to his squaw if she recovered; if she died, he was to give his life. She died not long after, in Four Mile Township, but Mike had made his get-away.

What the motive of the Indians was for their action will never be known, but the settlers were finally convinced that it was a scheme to frighten them from their homes, yet fearing more desperate means, even massacre, might follow, they at once ordered the Indians to leave the county, and never come back, with such positiveness and determination they went, and thus ended an event subsequently often recalled by the participants with humor, but to the actual terror, suffering and anguish of that one night, even massacre would not have added a single pang.

Life in the early days was fraught with many hardships and privations. Fever and ague were often prevalent, which would wrench and rack every bone in the body, debilitating the system, and making life miserable. The nearest physician was Doctor Grimmel, at The Fort, and to get him often required great exposure to the elements. Sometimes the flour sack got empty, and the nearest mill was at Oskaloosa, sixty-two miles away, requiring a week to make the trip. “Meanwhile,” said Isaiah one day, “we lived on ’coon and squash.”

As Isaiah grew to manhood, he very early identified himself with every enterprise to improve the social condition of the community. The church and school were objects of his special endeavor. A man of kindly impulses, intelligence, business capacity, public-spiritedness, and integrity, he became one of the most progressive and substantial citizens of the county. He laid out and organized the old, or first, town of Elkhart, and boosted it with great energy as the nucleus of the new Seat of Government when it was removed from Iowa City. He was early elected Township Trustee, held the office fifteen years, and in the meantime the entire list of township offices from Constable to the highest, the duties of which he most faithfully executed six days in the week, and on the seventh preached the Gospel according to the Campbellite, or Christian, Church, of which he was an exemplary minister.

The log cabin in which he resided many years, and in which the United States Government Surveyors made their home when running the lines for civil townships, long ago was supplanted by a fine, commodious residence, which, with his broad, productive acres, splendid orchard of fifteen acres, and fine vineyard, formed the environments of a home gratifying to the taste of the most fastidious, and there he is passing the evening of his life, in contentment and repose, with the consciousness of duty well done, and the esteem of all who know him.

Politically, he is a Republican. He cast his first vote for President for Lincoln. In local affairs, the prevailing sentiment in his favor is so nearly unanimous, his consent to take a public office is all that is necessary.

April Twenty-second, 1906.

Click here for a PDF document of this biography - Easy printing and page numbers for reference.

Copyright © 1996

The IAGenWeb Project

IAGenWeb Terms, Conditions & Disclaimer