|

ANDERSONVILLE PRISON

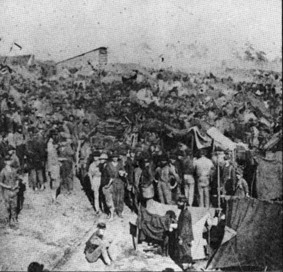

Of all the Civil War prisons none have compared to the notoriety of Andersonville, a small station located sixty miles south

of Macon in southern Georgia. Originally those twenty-seven acres was covered with a heavy pine forest. With

Generals GRANT and SHERMAN leading Union troops deeper into the South and the heart of the Confederacy, Southern Georgia

seemed to be the most secure place to confine prisoners of war. With the station a half mile away and surrounded by

swamp with a cover of pine, the site seemed ideal. Slaves cut down the trees, hew the logs, erected the stockade walls,

and dug a 5-feet deep trench. Later, if a prisoner approached this trench, he was shot dead by guards stationed in sentry boxes

thirty yards apart on the inside of the stockade. Once construction had been completed, what remained for the incarcerated was seventeen acres of ground which

included a wide swamp stretching back on either side of Sweetwater Creek. The creek ran through the stockade. Originally,

the stockade was intended to hold 10,000 prisoners. The first 500 prisoners arrived at Andersonville [officially named

Camp Sumter] in February of

1864. Using left-over materials, these men erected rude huts to shelter themselves from the sun and rain. As more prisoners

arrived, there wasn't much left to offer any kind of shelter. Then, early in March of 1864, the spring rain began to fall.

One inmate later said, "For dreary hours that lengthened into weary days and nights, and these again into never ending weeks,

the driving, drenching floods of rain poured down upon the sodden earth, searching the very marrow of the 5,000 houseless,

unsheltered men against whose chilled bodies it beat with pitiless monotony, and soaked the sand banks upon which we lay

until they were like huge sponges filled with ice water. An hour of sunshine would be followed by a day of steady pelting

rain drops. The condition of most of the soldiers who had no shelter was pitiable beyond description. They sat or lay on

the hillsides all day and night and took the pelting of the cold rain with such gloomy composure as soldiers learn to

muster. One can brace up against the cold winds, but the pelting of an all day and all night chilling rain seems to

penetrate to the very marrow of our bones."

One inmate later said, "For dreary hours that lengthened into weary days and nights, and these again into never ending weeks,

the driving, drenching floods of rain poured down upon the sodden earth, searching the very marrow of the 5,000 houseless,

unsheltered men against whose chilled bodies it beat with pitiless monotony, and soaked the sand banks upon which we lay

until they were like huge sponges filled with ice water. An hour of sunshine would be followed by a day of steady pelting

rain drops. The condition of most of the soldiers who had no shelter was pitiable beyond description. They sat or lay on

the hillsides all day and night and took the pelting of the cold rain with such gloomy composure as soldiers learn to

muster. One can brace up against the cold winds, but the pelting of an all day and all night chilling rain seems to

penetrate to the very marrow of our bones." Although Andersonville was surrounded by dense forest, no wood was furnished

to the prisoners so they could build some sort of shelter or a fire to warm themselves. Exposure to the rain, cold and heat

brought on disease which claimed thousands of lives. In March of 1864 there were 4, 603 prisoners of which 283 died

mainly from exposure. April claimed another 576 lives, an average of 19 deaths a day. Morning routine included the gathering

up of those who had died during the night. In May the hot sand was crawling with lice. A few tents were pitched with

pine leaves for bedding, located in the northeastern corner of the stockade and serving as a hospital. However there wasn't any nursing, remedies,

nourishing food, or even a change of clothing for the sick and dying prisoners.

With the arrival of summer, temperatures

often ranged above 100-degrees in the shade. The only source of water was from Sweetwater Creek, pictured at right, which had become polluted

from an encampment of 3,000 Confederate guards stationed upstream. Those who were strong enough dug holes in the ground, seeking

shelter within the burrows. By this time, 70% of those taken to the "hospital" died. By the end of May there were 18,454 prisoners

at Andersonville.

With the arrival of summer, temperatures

often ranged above 100-degrees in the shade. The only source of water was from Sweetwater Creek, pictured at right, which had become polluted

from an encampment of 3,000 Confederate guards stationed upstream. Those who were strong enough dug holes in the ground, seeking

shelter within the burrows. By this time, 70% of those taken to the "hospital" died. By the end of May there were 18,454 prisoners

at Andersonville. All of the drinking and cooking water available to the prisoners came from Sweetwater Creek, the only

drainage of two camps of guards and the prisoners, numbering more than 20,000 people. When some prisoners attempted to

obtain water where it began to flow into the camp, they were shot dead because they were too close to the "dead line"

trench. Each man was allowed daily rations of a cake of corn bread, half the size of a brick, made from coarsely ground

and unsifted meal.

Sometimes there was a small slice of salt pork and on occasion a few beans. Because the hulls of the meal were coarse

and harsh, a majority of the prisoners experienced every sort of imaginable intestinal complaint along with scurvy and hospital

gangrene. In less than seven months 9,379 of the prisoners had died. Dr. Joseph JONES, a Confederate surgeon from Atlanta,

Georgia, visited Andersonville in August. His report stated, "In June there were 22,291, in July 29,030, and in August 32,899 prisoners confined in the stockade. No shade tree was left in the entire enclosure. But many of the Federal prisoners had ingeniously constructed huts and caves to shelter themselves from the rain, sun and night damps. The stench arising from this dense population crowded together here, performing all the duties of life, was horrible in the extreme. The accommodations for the sick were so defective, and the condition of the others so pitiable that from February 24th to September 21st nine thousand four hundred and seventy-nine died, or nearly one-third of the entire number in the stockade. There were nearly 5,000 prisoners seriously ill, and the deaths exceeded one hundred per day. Large numbers were walking about who were not reported sick, who were suffering from severe and incurable diarrhea and scurvy. I visited 2,000 sick lying under some long sheds. Only one medical officer was in attendance—whereas at least twenty should have been employed. From the crowded condition, bad diet, unbearable filth, dejected appearance of the prisoners, their systems had become so disordered that the slightest abrasion of the skin from heat of the sun or even a mosquito bite, they took on rapid and frightful ulceration and gangrene. The continuous use of salt meats, imperfectly cured, and their total deprivation of vegetables and fruit, caused the scurvy. The sick were lying upon the bare floors of open sheds, without even straw to rest upon. These haggard, dejected, living skeletons, crying for medical aid and food, and the ghastly corpses with glazed eyeballs, staring up into vacant space, with flies swarming down their open mouths and over their rags infested with swarms of lice and maggots, as they lay among the sick and dying—formed a picture of helpless, hopeless misery, impossible for words to portray. Millions of flies swarmed over everything and covered the faces of the sick patients, and crowded down their open mouths, depositing their maggots in the gangrenous wounds of the living and in the mouths of the dead. These abuses were due to the total absence of any system or any sanitary regulations. When a patient died, he was laid in front of his tent if he had one, and often remained there for hours."

Of the 42,686 prisoners incarcerated at Andersonville, 12,853 had been carried out to their graves within one year.

10,982 died between February 27, 1864, and October 20, 1864, or in less than eight months, at a rate of over

1,372 a month - an average of 45 deaths per day, or two for each hour of the day and night.

The total number of graves in Andersonville's cemetery is 13,701. Of these gravesites, 12,779 have names on the headstones, while 922 are

unknown graves. Of the dead buried here 12,853 were from the Andersonville stockade. 848 were brought from

adjacent localities and laid in the National Cemetery. The first victim of Andersonville was Adam SWARNER, of New York,

who died February 27, 1864 - his headstone marked No. 1 and his grave is the first of the long row which

begins in the southeast corner of the cemetery. Adam's brother Jacob SWANER died five months later and was interred in

grave number 4,005. The last victim died on November 30, 1865 with his headstone numbered

12,853 and is the last of the long rows of graves. His name was John KING, also from New York.

When the Confederacy collapsed in April of 1865, Dr. Heinrich Hartman "Henry" WIRZ, the Swiss commander of Andersonville, was still residing with his family in his quarters at Andersonville.

Dr. WIRZ stood trial for war crimes and was hung on November 10, 1865. His was the only conviction for the atrocities of

Andersonville, and he was the only man who was tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes during the Civil War. Historians have attributed some of the problems at Andersonville to the fact that supplies and rations

in the South were near depletion. What was available went to the troops instead of prisoners. Additionally,

the population of those incarcerated at Andersonville far exceeded what anyone could have ever anticipated. Dr. WIRZ's conviction remains

controversial to the present day with many believing that he was dealing with events and circumstances that were well

beyond his control. However, his trial has established a precedent that certain wartime behavior is unacceptable regardless of

how it was committed, either by direct orders from superior officers or by one's own actions. Toward the close of the Civil War,

Clara BARTON [Clarissa Harlowe BARTON (1821-1912)] received permission from President Abraham

LINCOLN to start the Office of Correspondence with friends of the Missing of the Union Army. This office provided the lists

of missing soldiers which were published in newspapers along with the names of the known dead from various battles. If someone

contacted Clara BARTON, she would attempt to locate missing soldiers. Dorence ATWATER (1845-1910), a former prisoner of war who had

been incarcerated at Andersonville, learned of Miss BARTON's work and contacted her. Dorence had smuggled out of the

prison a list of the Union soldiers who had died while at Andersonville, all of which he had meticulously recorded. Convinced

that Dorence ATWATER's list was of great importance to her cause, Miss BARTON secured permission from the War Department to return to

Andersonville and permanently mark the graves there. Dorence and Miss

BARTON, along with a crew of 40 workers under the supervision of Captain James MOORE, intensively marked each grave using ATWATER's list as a guide. When their work

was completed, only 460 graves had been marked as "unknown Union soldier" primarily due to the accuracy of ATWATER's list.

Miss BARTON raised the flag over the newly

established Andersonville National Cemetery on August 17, 1865.

Clara BARTON and Dorence ATWATER became lifelong

friends, often speaking together when giving lectures on Andersonville's cemetery and prison.

The War Department had misunderstood Dorence ATWATER's intention for his secret list of the

deceased at Andersonville. The list was confiscated and later used as evidence against Henry WIRZ during his trial and

subsequent conviction of war crimes. ATWATER regained possession of the list and refused to return it to the War Department.

Consequently, ATWATER was arrested, court-martialed, and incarcerated at the Albany Penitentiary. Clara BARTON and

Horace GREELEY, among others, petitioned for ATWATER's release. GREELEY fulfilled ATWATER's goal of publishing the list

on February 14, 1866. ATWATER was appointed as the U.S. Consul to the Seychelles Islands and later as the Consulate in

Tahiti. He was interred in a churchyard at the village of Papara, located on the southern coast of Tahiti. His gravestone

bears the epitaph "Tupuataroa" which means a "wise man."

Due to Clara BARTON's

work providing supplies and nursing to soldiers during the Civil War, she has been called the "angel of the

battlefield." She also was the co-founder of the American Red Cross.

Dorence ATWATER, Clara BARTON, Andersonville Cemetery

RINGGOLD COUNTY SOLDIERS AT ANDERSONVILLE

* Denotes Soldier died while incarcerated

| SOLDIER'S NAME |

RANK & REGIMENT |

CAPTURED |

DEATH & INTERMENT

or PRISONER EXCHANGE |

ANDREWS

H. C. |

Co. B 8th IA Cavalry |

Newnan GA |

Prisoner exchange |

BECK

Pvt. James |

Co. K 13th IA Infantry |

22 Jul 1864

Atlanta GA |

Prisoner exchange |

| * COOPER, Corporal Silas |

Co. B 5th IA Infantry |

Missionary Ridge TN

25 Nov 1864 |

09 Jul 1864

died of Scorbutus

Nat'l Cemetery

Andersonville GA

Grave 5101 |

CULVER,

Sgt. W. B. |

Co. D 8th IA Infantry |

|

19 Sep 1864

Exchanged at Atlanta GA |

* CULVER,

Pvt. William |

Co. D 8th IA Cavalry |

|

02 Oct 1864

Nat'l Cemetery

Andersonville GA |

FOSTER,

Pvt. Lexington |

Co. B 60th OH Infantry |

|

Sent to Millen GA

11 Nov 1864 |

McGUGIN

Frank |

Co. A 30th OH Infantry |

|

Escaped per obiturary

Prisoner exchange

Atlanta GA

19 Sep 1864 |

* ROGERS,

Pvt. Alexander |

Co. G 29th IA Infantry |

14 Mar 1864

Claysville AL |

29 Sep 1864

Nat'l Cemetery

Andersonville GA

Grave 10017 |

* RUSSELL,

Elias W. |

Co. G 4th IA Infantry |

14 Mar 1864

Claysville AL |

12 Dec 1864

died of Scorbutus

Nat'l Cemetery

Andersonville GA

Grave 12264 |

Hon. B. F. GUE wrote an article about his visit to Andersonville Prison in 1884 which was

published July 3, 1884 of Annals of Iowa.

Hon. GUE's article appears on IAGenWeb's History Project.

Kevin FRYE lives 40 miles from Andersonville, Georgia. He conducts lookups at no charge and maintains an

Andersonville website. Kevin does charge a

small fee to cover his expenses if one requests a photograph.

SOURCES:

GUE, Hon. B. F. "Iowa and Andersonville" Annals Of Iowa Vol. II. No. 3. Iowa Historical Society. Des Moines. July 3, 1884.

http://www.nps.gov/ande/index.htm

Photographs courtesy of the Library of Congress

Transcription and compilation by Sharon R. Becker, May of 2009

Iowa in the Civil War

An Iowa GenWeb Special Project, this site promotes the people, events, and genealogy of Iowa Regiments in the Civil War. This project includes a searchable database. To access the home page of Iowa in the Civil War Project, go to: iagenweb.org/civilwar/

|