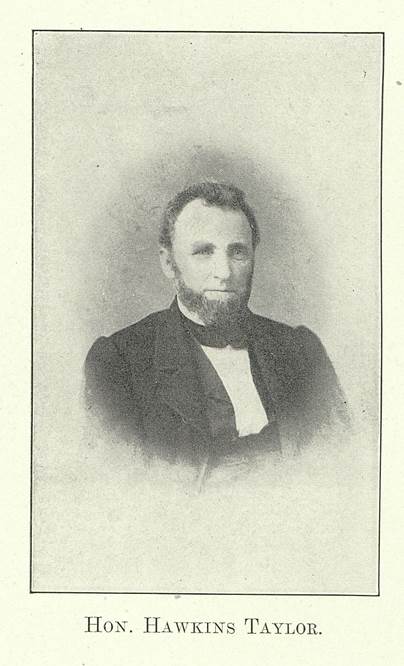

Hawkins Taylor: In the Thick of Things

TAYLOR, WALKER, CASEY, GILBERT, PATTERSON, JOHNSON, STOTTS, COTTON, HUNSAKER, ALLEN, ALPHIAN, POAGE, CRUICKSHANK, SMITH, YOUNG, MILLER, HODGES, BROCKMAN, CLEMENSTWAIN, LINCOLN, JACKSON, MCDOWELL, HAYES, BELKNAP

Posted By: John Stuekerjuergen (email)

Date: 10/25/2014 at 09:55:57

Hawkins Taylor: In the Thick of Things

by John StuekerjuergenHe was not only a founder of West Point, Iowa, but a frontiersman, lead miner, farmer, territorial legislator, sheriff, mayor, and friend of a U.S. President. Parts of his life are well documented, and other parts are a mystery. But it’s clear he was a man of action, who earned the rewards and suffered the punishments that go with that trait. And he certainly had to have been one of the most colorful characters in the history of Lee County. This article covers the time from his childhood to his last years in the nation’s capital. It is based on information extracted from Taylor’s memoirs at Western Illinois University and from various on-line resources.

Early Years in Kentucky

Hawkins Taylor was born on a farm in hilly and heavily timbered Barren County, Kentucky on Friday, November 15, 1811. His father, Samuel, was born in Antrim County, Ireland and immigrated to the United States in 1781. Samuel married Catherine Walker at an Irish Presbyterian settlement in Rockbridge County, Virginia in 1790. Hawkins said his “Mammy” had no health after his birth, and died after a lingering illness in 1822. He later theorized that “her purity and her prayers (have) been all that has saved me in this world from destruction, for I have been, all my life, impulsive and a leader, and being thrown all my life in the midst of temptations…her ministering spirit has saved me.”

Hawkins, his older brothers, James and John, and their father were left to a hard life. He did most of the cooking, and helped to cut and trim logs for sale to the public. James provided most of the farm labor. The family had no books, and there was no school in the area. No stage coach had passed within 40 miles of his home. And he had encountered but one or two newspapers. As Hawkins later reminisced, “few boys had seen or knew less of the world than I did.” John did receive some formal education after he left home, and returned to teach Hawkins over the course of three months. The section on Pike’s Arithmetic took just 19 days. Despite the limited education, Hawkins did admit to an intense interest in politics, and that would later change his life.

600 Miles on Horseback

As he approached adulthood, Taylor learned the tanner’s trade. He left Kentucky for Missouri in April 1831 with a horse, saddle, bridle, and $29, hoping to find work in the West. He had never before been outside the immediate area of his home community, and did not know what he would do after he arrived. However, he was told he had a cousin in St. Louis, the sheriff of the county, and also had a known acquaintance in Hannibal. He made the journey, 600 miles, by himself in two weeks and found it miserable. The dirt roads meandered, and there were few bridges across the many streams and rivers. He often had to swim.

Upon arrival in St. Louis, then a town of 6,000, Taylor found the home of John K. Walker, his cousin. Rather than a warm welcome, Taylor received a suspicious look and hard questions from a man he had never met. By that time, as Taylor recalled, “my foolish Scotch-Irish blood was up.” It took a few minutes of questioning before Walker satisfied himself of young Taylor’s identify, and tempers cooled. Walker invited him into the house, and Taylor stayed with the family for three days before pushing on to Hannibal and his friend. After staying there a week, homesick and not knowing what to do, he went back to Kentucky.

Back home, as he recalled, he was given an opportunity to make a living. However, he “could not, after seeing the new country, bear to remain in the old.” After about a month, he again set out for Missouri. Crossing into Indiana, it then rained on him every day until he reached his destination. He found shelter only one night, when he stayed in an abandoned log cabin, full of rats. The Grand Prairie, a 30-mile stretch in Illinois, was the “terror of all travelers.” It was without timber or settlement, and green-headed flies were so bad in summer they had killed some horses that attempted the crossing. Taylor pushed on to Marion County, Missouri, where he stayed with his distant cousin, William Patterson, near Quincy.

In the fall months, Taylor worked in a brick yard for $12 a month. He soon had charge of the yard. In the winter, he cleared ground for Patterson “from the time I could see in the morning, until dark at night. I would work before breakfast.”

Lead Mining and Indian Attacks

By spring 1832, Taylor had again become restless. He traveled upriver by boat to the Galena lead mines with Hayden Gilbert, who had previously made some money there. Because the river was so low that year, he had to switch from the Chieftain to another boat at the rapids. There was a new discovery at Snake Hollow, about 30 miles outside Galena, which caused great excitement. 150 men were already working there. Taylor took up several mineral claims and went to work. He and the other men cooked for themselves, living on bread, coffee, and mess pork. They built a log cabin, covering it with bark, and had double bunks. Comfort was provided by a rough blanket placed over straw. “It was a healthy, rugged, and happy life.”

While Taylor was near Galena, the Sauk and Fox tribes, under the leadership of Black Hawk, were trying to avoid expulsion from the state of Illinois. One night, a frantic messenger told the miners that Indians had attacked and defeated Major Stillman on May 14, about 70 miles east, and were headed in the general direction of the camp. This, of course, generated intense excitement. A militia had been enlisted in Illinois and General Scott and his regulars were coming from the east, but no soldiers had yet arrived. The miners were on their own.

Despite some belligerent talk, most fled to Galena within an hour. Hawkins rode to a smaller settlement nearby. He agreed to protect the store of a merchant, who then left to join a cavalry unit in Galena. Over the next week, Hawkins “was taken with the ague (alternating chills and fever), and had the regular shakes every other day.” He did not encounter any Indians, but their attacks in the area continued. Taylor and an estimated 2,000 other miners were bottled up in Galena for two weeks, with nothing to do. As it was impossible to determine when the Indian hostilities would end, he returned to William Patterson’s home in Missouri.

The First Farm at Irish Grove

In fall 1832, Taylor worked in a tanning yard in Hannibal for $15 a month. He had a slight attack of cholera, and did not recover completely until winter. Patterson, his cousin, had been talking about prospects for a better life at an Illinois settlement of former Kentuckians. It was Irish Grove, in Sangamon County (now Menard County), northwest of Springfield. Patterson, Taylor, and a man named John Johnson left from Hannibal. As Black Hawk had surrendered, Taylor expected to winter in Irish Grove and go back to Galena’s lead mines in the spring. He was hired by William Stotts, an old acquaintance. Although in bad health, he continued working.

When offered the chance to visit his family in Kentucky, Taylor declined. He wrote that “I was as homesick as anybody ever was, but had made nothing and I did not mean to go back until I did make something.” That winter, he determined to start farming and “give up the mines.” He went to Springfield and borrowed $50 from a total stranger and “entered 40 acres of timber land in the bottom of Salt Creek.” [Note: The land deed is remarkable because of the witness’ signature, discussed later in this article]. Taylor boarded at John Patterson’s, two miles from his claim. He took breakfast at dawn, and then carried a piece of cornbread and some meat into the government-owned timber, where he felled trees and trimmed rails until it was too dark to see. By winter’s end, he had made enough rails to fence two sides of a 40-acre field.

Log House, Marriage, Child

In the fall and winter of 1833, Taylor built a log house at Irish Grove, 18 feet square, with a puncheon (plank) floor and brick chimney, doing all the work himself. He also added 20 acres to his farm, and built a stable. The house was almost destroyed by a prairie fire in November. Taylor was awakened by a great roaring and bright light about 2 a.m. Looking out his cabin door, he saw fire about 15 miles away. Such fires were very common and dangerous at the time because of the height, thickness, and expanse of the prairie grass. Moving quickly, Taylor and a neighbor set a series of back fires that saved their homes.

In spring 1834, Taylor married Melinda Walker, a cousin. “She was very handsome and truly good in every sense of the term.” In addition to their new home and land, they had only one little pony and two yoke of oxen. Taylor planted corn that year, needing a good crop to service his land loan. However, in the latter part of the year he became terribly sick and was confined to his bed for two months. It seemed that his doctor and most of his friends had given him up for dead. He slowly recovered but, by that time, someone’s hogs had eaten his corn. He was able to salvage his finances by selling his farm, with improvements, to a new arrival from New Jersey for $400. He invested that money in a larger piece of land.

The first child of the new marriage, Catherine Esther, was born in spring 1835. Taylor recalls that “nobody was really well; all were full of malarial fever.” Irish Grove was increasingly seen by the settlers as an unhealthy place to live. In early 1836, Hawkins and three relatives (William Patterson, Green Casey, and Alexander Walker) started to look west of the Mississippi River, to what was then part of Michigan Territory, and would thereafter became part of Wisconsin Territory and then Iowa Territory.

On to Iowa, and West Point

The resolution of the Black Hawk wars had opened up the land in what is now Iowa to settlement. In 1836, the population west of the Mississippi River valley was minimal and vast tracts of land were available. On May 9, Taylor and his three relatives crossed the river at Ft. Madison to take a look. The group of four traveled on horseback, with saddlebags, in the “regular southern style.” An old man named White and his son-in-law operated the ferry. There were then only 100 people living in Ft. Madison, and less than 3,000 in what is now the state of Iowa. Taylor landed near the current-day approach to the river bridge in Ft. Madison. The charred remains of the old fort were still visible to the west. The lower part of the town was covered by “as fine a growth of large oak timber as (Taylor) ever saw.”

The group spent most of the day in Ft. Madison. They learned that settlers in the countryside would meet together and make regulations to govern themselves. By those regulations, one settler was allowed 160 acres of prairie and the same of timber for each claim. In order to retain the claim, it was necessary to “break” five acres and build a cabin in short order. “The settlers were a law unto themselves,” as Taylor recalled.

In Taylor’s own words: “We went on from Ft. Madison to Dr. Gilmers, an old Kentucky friend of ours who lived two miles from town. He had been there over a year, being one of the earliest settlers. The doctor had a log cabin. We all comfortably lodged in that room. Patterson and I went on to (what is now called) West Point, ten miles from the river. The town had just been laid out and had only one house on it, and that was about 15 feet square, made of split hickory logs, the split sides in and clabboards (clapboards) nailed over the cracks and clabboard roof. It was occupied by a store [owned by John L. Cotton]. There were three pieces of calico, a few pieces of domestic goods, a few trinkets, a barrel of whiskey, some sugar and coffee.”

“The town was laid out on the prairie at a point of timber, a beautiful site for a town, high with a grand view, west and north. The streams were much lower than the prairie so that the views extended miles and miles to the timber of the Skunk and Des Moines Rivers. We bought out the town site from Abraham Hunsaker(?) for $1,500, and all located and bought claims for farming adjoining. We at once advertised a sale of lots to take place on September 11, and returned…to Illinois. I sold out my land in Illinois at a handsome profit on cost, making me worth then about $1,500.”

“I at once returned to West Point, and John Allen, Casey, and two of Mr. Walker’s sons went with me. We took a team and went to work to build a house (for each of our families). The houses were frame 18x32 feet, one story high. We had no lumber of any kind, and could get none. We split out the studding, made puncheon floors, and clabboard doors. We got the frames up, covered, and weather-boarded by the time of the (lot) sale.”

First Sale of Lots in West Point

It was well known that settlers in the area enjoyed their whiskey. “In fact, it was hardly allowable for a man to…live in the country who did not use whiskey.” The expectation at an event of this type was that the lot sellers would provide free drink to potential bidders. As Taylor was a teetotaler (as probably were some of his relatives), he attempted to offset the lack of alcohol by holding a barbecue. Luke Alphian, “a noted Kentuckian fighter and the leading settler of that part,” roasted the ox. There was also plenty of bread, and the sale went off most happily. More than $2,000 of lots were sold, and that was for a very small part of the town. About 200 people attended the sale, many with their families. Also present were a dozen candidates for the legislature of Wisconsin Territory, which had just been organized.

Taylor went back to Irish Grove shortly after the sale, and brought his family to West Point. By that time, there were about a dozen families in town. There were no sidewalks, only grass paths between the buildings. Taylor joined Cyrus Poage in opening a store. Poage went to St. Louis and bought a small stock of goods, but the boat bringing the stock upriver was caught in the ice due to an early freeze. Taylor had to send a team down to Clarksville to salvage the stock, which cost them more than the goods were worth. That year there was very great immigration to the West Point area, little grain production, and the early river freeze cut off all boat traffic. The result was short rations. So food and other supplies had to be purchased in Illinois at enormous prices, and hauled more than 100 miles.

The Taylors’ second child, Mary Jane, was born at West Point in January 1837. The third, James, died after a few months. The fourth, Anne Elizabeth, was born in January 1840. The fifth, Samuel David, was born in 1842, after they had moved to Ft. Madison.

Settling in at West Point

The move to West Point seemed to have done wonders for Taylor’s health. In August 1839, he commenced to lay out his farm. He was at that time 5’10” and 160 pounds. He was “full of vigor” and worked from daylight until dark all fall and into the winter. With a hired man, he built a farm house 18x32 square feet, with a back building the entire length, a cellar under one room, and shingle roof. He hired the building of the doors and the plastering after he had nailed on the lathe. He built a double chimney and dug and walled a well 36 feet deep. There was also a building, 30 feet square, that served as a barn, corn crib, and stable. The snow was about a foot deep throughout December and January, and into part of February. But they accomplished what they had intended. By April of the next year, he was farming 170 acres.

Of living in pioneer Iowa, Taylor noted that “the only settlements in the county were in the timber or on the edge of the prairie. Few of the settlers had the means to break the prairies. In the timber, they could clear little patches and fish, hunt, and live.” Upon arrival, the first objective was to plant corn, and then fence the ground. “As was the case in Kentucky, it was the custom to ride into town on Saturday nights. Settlers would hitch their ponies to the racks in front of all the stores and public places and have a good time, drinking the purest rot gut whiskey ever made, and occasionally have a friendly fight to test the manhood of different neighborhood bullies.” Ultimately, though, “every man helped his neighbors and divided what he had with his neighbors. If one man lost his horse or his oxen, his neighbors went and plowed his ground for him.”

During his time in West Point, Taylor often stopped at Black Hawk’s winter camp on Devil’s Creek and bought little cakes of sugar from his wife and daughter. He noted the women appeared to be thoroughly broken down in hope and feeling after the Indians’ military defeat. In his final years, Black Hawk was seen on at least one occasion in West Point, still holding his head high. However, he died beside the Des Moines River in 1838.

It should be mentioned here that Taylor also had some interesting anecdotes about fellow settler Alexander Cruickshank and about the rainy day in fall 1838 when the land in West Point Township was sold at Burlington, the territorial capital. Readers should be aware these writings exist. However, they are too lengthy to include here.

Territorial Legislator

From age 14, Taylor had taken an active interest in politics. He was a Whig and, later, a Republican. In the fall of 1836, when in West Point, he was elected county clerk of court. He was appointed a justice of the peace by Governor Dodge in 1837. He “tried a few cases and married a few couples.” When the Iowa Territory was formed in 1838, one of the first necessary acts was to elect a legislature. There were many candidates, and Taylor was one. In October, he distributed a one-page campaign circular to the voters of Lee County, Iowa Territory. He expressed support for a system of “common” (public) schools, extension of the boundary of Lee County northward to include Denmark and the area between it and the Skunk River, and the selection of West Point as the county seat. Taylor was popular with the electorate, and he and his cousin, William Patterson (also of West Point), won 2 of the 26 seats in the House of Representatives. His first two campaign planks were accomplished, but the third only for a short time.

Frontier Sheriff

After a “hot contest,” Taylor was elected Sheriff of Lee County in 1840. By law, he was required to live in Ft. Madison, and so he moved his family. He found this a difficult job, as many of the early settlers had independent streaks and a lack of respect for law enforcement. Keokuk, for example, had a reputation for being a rough town in its earliest days. Of the few hundred residents of Keokuk, almost all were engaged in the lighting of freight over the rapids. Among their numbers were “the worst class of men that could be found, murders and gamblers and thieves of every class.” Nauvoo, a much larger town at that time, was “infected…with a great number of thieves, who would cross over to Iowa and commit depredations.” They would then return to Nauvoo, protected by the populace there. Taylor was successful in making friends in the various towns who supplied him with information and assisted him in making arrests. On one occasion, he achieved temporary fame by arresting Hyrum Smith, brother of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet.

In later years, Ann Eliza Young, wife no. 19 of Brigham Young, reflected back on the Mormons’ troubles. “I was talking with a person who was with the Mormons in Missouri and Illinois. He said that Joseph (Smith) not only advised his people publicly to plunder from the Gentiles, but privately ordered them to do so. At one time, he was sent himself by the Prophet to steal lumber for coffins. He went with a party of men down the river, loaded a raft with lumber from a Gentile saw-mill, and brought it up to the “City of Saints.”

The Battle of Nauvoo

During the time Taylor was Sheriff, the Mormon population of Nauvoo and Lee County increased so rapidly that non-Mormons felt their political and religious influence threatened. Within just a few years, Nauvoo had 12,000 residents. Of Nauvoo, Taylor said “it was the most beautiful town site I ever saw. The temple was built on the high ground above the middle of the town plat, and was a perfect building.” The construction of the temple required large numbers of skilled laborers, and they poured in from New England. “There was no idling, no profanity, or drunkenness.” However, there was insufficient food for the burgeoning population. Taylor alleged that numerous residents stole from outlying farms in Hancock and Lee Counties, with the latter preferred due to its less-established law enforcement.

The number of nighttime robberies in Lee County became so high they became the primary topic of conversation. When Taylor or his deputies crossed the river and attempted to arrest the alleged thieves, they were surrounded by Nauvoo men who held knives and sticks, pretending to whittle. The threat was clear, and the law men invariably left without their prisoners. Lee County residents were also aghast at the May 1845 murders of the preacher, John Miller, and his son-in-law near West Point by the Hodges brothers of Nauvoo. The suspects were apprehended in that instance, but the tension between Mormons and non-Mormons bordered on violence.

By the end of 1845, it became clear there was no possibility for peace. The citizens of four Illinois counties determined to drive the Mormons from Nauvoo. Representatives met in convention and prepared lists of Mormon families living outside the town. One by one, the families were ordered to remove the contents of their homes, which were then set afire. Eventually, Taylor claimed that some 1,500 homes were burned and their occupants driven into Nauvoo.

The anti-Mormons then organized an army of several thousand and marched on Nauvoo. Said Taylor, “I most foolishly and wickedly, with a few others, had gone over to Keokuk and had joined the anti-Mormon army and was given a U.S. musket that had been captured with some hundred others from the Mormons at Keokuk.” The “army” was commanded by General Brockman, a minister. About 1,500 had firearms of some kind, including six small cannon. The Mormons met them at the edge of the city, and the ensuing battle lasted several hours. The momentum flowed back and forth, and there were about a “half dozen killed and double as many wounded.” Taylor later found a bullet hole through the leg of his pants.

Under siege, the Mormons had no means of feeding the town and within a few days became demoralized. They entered into a compact to vacate the town by May 1846. That allowed the anti-Mormon army to disband, and led to the famed westward trek of the Mormons.

Mayor of Keokuk

After Taylor completed his term as Sheriff, he moved back to West Point in 1846. However, after just two years there he was asked to relocate to Keokuk to manage the county court proceedings. By that time, Keokuk was one of the largest and most prosperous cities on the upper Mississippi. Taylor was later involved there in brick-making, construction, and real estate sales. He was elected Mayor in 1857, and he and his wife became principal members of the town’s society. In 1859, their home was on the southeast corner of Exchange and 8th Streets. They owned a second home or summer cottage along the river north of town, and Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) was a guest there on at least one occasion. Clemens was known to be enchanted with Taylor’s daughter, Annie, who was born at West Point. He corresponded with her while she attended Iowa Wesleyan College in Mt. Pleasant (to which Clemens referred as “Mt. Unpleasant).” In one of his letters, he hinted that his brother, Henry Clemens, was equally taken with Annie’s older sister, Mary Jane.

In his later years, Hawkins Taylor reminisced that, in his opinion, the town of Keokuk had a more interesting history than any other town he had ever visited. A significant number of people from Keokuk filled major leadership positions at the state and national levels in the second half of the 19th century.

“Warm Friend” of Lincoln

Earlier mention was made of Taylor’s friendship with a U.S. president. At the age of 21, after his arrival at Irish Grove, Illinois, Taylor made the acquaintance of a young clerk at a store in nearby New Salem. He later asked the young man to witness the signing of the deed for his first farmland purchase on June 4, 1833. The young man was Abraham Lincoln. Both Taylor and Lincoln were natives of Kentucky.

In August, Taylor had an opportunity to return Lincoln’s favor. Lincoln was one of 15 or 20 candidates for the Illinois legislature. Taylor offered to work at the nearest polling place, which was 18 miles from Irish Grove. He arrived early in the morning, dripping wet with dew from riding through the tall grass, and immediately made himself useful.

Taylor was aware that voters in the area leaned toward Andrew Jackson, a Democrat, and were familiar with the candidates for Governor. However, they generally knew little about the legislative candidates. Most voters needed help in reading and completing their ballots, and Taylor was happy to provide it. He invariably asked to write in Lincoln’s name for the legislature. Whenever someone asked if Lincoln was a Jackson man, Taylor said (knowing better) that he reckoned so, but didn’t really know Lincoln’s politics. Taylor claimed that 108 of the 111 voters he assisted that day took his recommendation. Lincoln finished second in the overall polling but, since the top two candidates were elected to the legislature, he won his first political victory.

The two men were later described as “warm friends.” At least a dozen letters between them, written in the 1850s and 1860s, are in various libraries and museums. One letter from Lincoln to Taylor was on display at the Iowa Capitol in early 2008. When Lincoln became the Republican nominee for President in Chicago in 1860, Taylor was a convention delegate.

In 1862, Lincoln appointed Taylor chairman of a federal commission to evaluate payments claims from Missouri soldiers who remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. The commission became popularly known as the Hawkins Taylor Commission, and its actions had repercussions through the balance of the century. Much of the commission’s work was completed in St. Louis. During his time with the commission, Taylor expressed concern for a relative in the Union army. He wrote to Annie Wittenmyer, who organized care for wounded soldiers, that “In your glorious work of looking after the Iowa soldiers you may find a little nephew of mine who is with Col. J.A. McDowell of the 6th Iowa. If he is wounded try and see that he is properly cared for and if dead try and have Col. McDowell have the spot marked so that I may secure his body.”

In 1864, Lincoln appointed Taylor federal mail agent for the State of Kansas. However, he soon lost that job, reportedly due to the animosity of Postmaster General Montgomery Blair. Taylor suspected it was due to his own “radical” politics. A friend of Taylor’s wrote to Lincoln that Taylor was without a job, without money, and with a sickly family on his hands. It was clear that Taylor’s life of high adventure had not made him a wealthy man. There is no indication that Lincoln provided any assistance.

Taylor in Washington

Taylor moved to Washington City (now Washington, DC) in 1868, and became prominent in political and social circles there. When asked his business, he replied, “I do anything which ought to be done, and for which I will be paid.” He became known for his influence with national leaders. The diary of President-elect Rutherford B. Hayes, for example, recorded that “Mr. Hawkins Taylor seemed to have many friends.” Taylor came within a few votes of being elected Door Keeper of the House, a very influential position at the time. However, the incumbent prevailed.

Functioning as a lobbyist, Taylor was known to accept payments for recommending certain individuals for political appointments. That got him caught up in the impeachment proceedings for General William Belknap, Secretary of War under President Grant, and an old friend from Keokuk. Belknap was accused of accepting payments for appointing traders at federal military posts. While it was legal for Taylor, as a lobbyist, to recommend appointments, it was illegal for Belknap, as a cabinet member, to accept payments to make them. Taylor was called to testify during the congressional hearings in 1876. The New York Times said his wit provided the “entertainment” that day. Asked if he followed the late Secretary of War to Washington, Taylor quickly retorted, “No, the Secretary followed me.” The Times referred to him as “an old gray-headed man, with cunning face, quick movement, imperturbable manner, and shabby-genteel air.” The son of the Kentucky backwoods would probably not have taken issue with that description.

Little else is known about Taylor’s later life, except that he was a prolific writer about Iowa history. He had an uncanny memory, and was frequently published in the Annals of Iowa. He died in Washington, DC in November 1893. His listed address was directly north of the U.S. Capitol.

Footnotes:

Melinda Walker, the spouse of Hawkins Taylor, was a sister of Alexander H. Walker, another founder of West Point, Iowa.Thanks to the State Historical Society of Iowa, Western Illinois University, Keokuk Savings Bank & Trust (Caleb Forbes Davis Collection), and to Vern Meierotto for his editing and for filling in some of the information gaps.

Lee Biographies maintained by Sherri Turner.

WebBBS 4.33 Genealogy Modification Package by WebJourneymen